The term “dPEG®” is Vector Laboratories’ trademarked acronym for “discrete polyethylene glycol” or “discrete PEG“. The “discrete” portion of the dPEG trademark indicates single molecular weight PEG technology and can help simplify product analysis. Comparatively, traditional PEGs are not single compounds.

Like traditional PEGs, our products contain an amphiphilic backbone of repeating ethylene oxide units. The term “amphiphilic” means that the compound is soluble in both water (or aqueous buffer) and organic solvents. All PEG products that do not contain hydrophobic substituents are soluble in water and in a variety of organic solvents. The addition of hydrophobic groups to PEG reduces the water solubility of some PEG products.

As part of Vector Laboratories’ BioDesign™ portfolio, dPEG was developed and continues to be manufactured using our proprietary synthetic and purification processes, ensuring lot-to-lot consistency and optimal performance.

Synthesis of quantum dots involves injecting solutions of the semiconductor metals into hot (>300°C) organic solvent, such as octadecene, and allowing the metals to nucleate (the first step of crystallization) and form alloys. For emission wavelengths of 470-720nm CdSe, CdTe, and InP alloys are used, while PbS and PbSe are utilized for emission wavelengths >900nm.

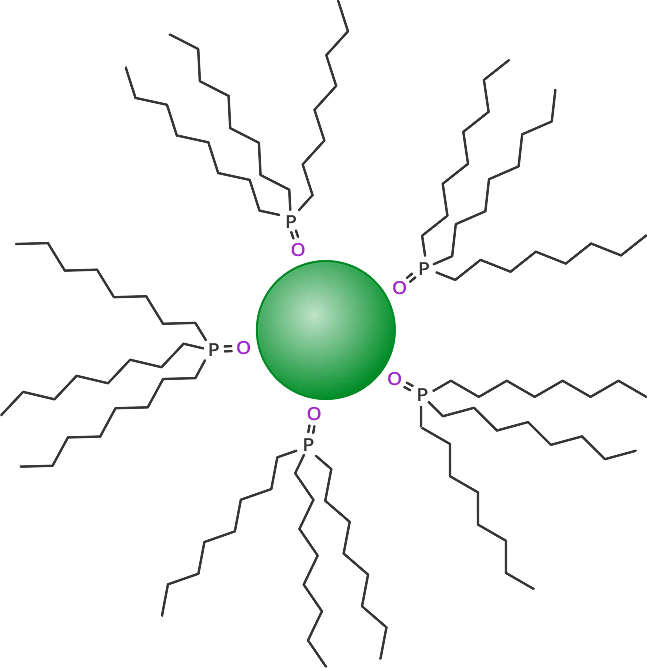

Water solubility is one of the major hurdles that must be overcome when producing quantum dots for biological applications. When the quantum dots have reached their desired size, the surface is coated so that they can be easily isolated. Originally this was done using tri-n-octylphosphine oxide (TOPO) which results in a very hydrophobic quantum dot (Figure 1).

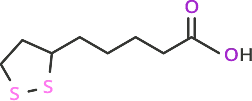

thioctic acid, also known as lipoic acid

Chemical Formula: C8H14O2S2

Molecular Weight: 206.33

cyctamine, also known as

2,2’-disulfanediyldiethanamine

Chemical Formula: C4H12N2S4

Molecular Weight: 152.28

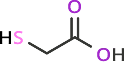

2-mercaptoacetic acid

Chemical Formula: C2H11NO2S2

Molecular Weight: 169.27

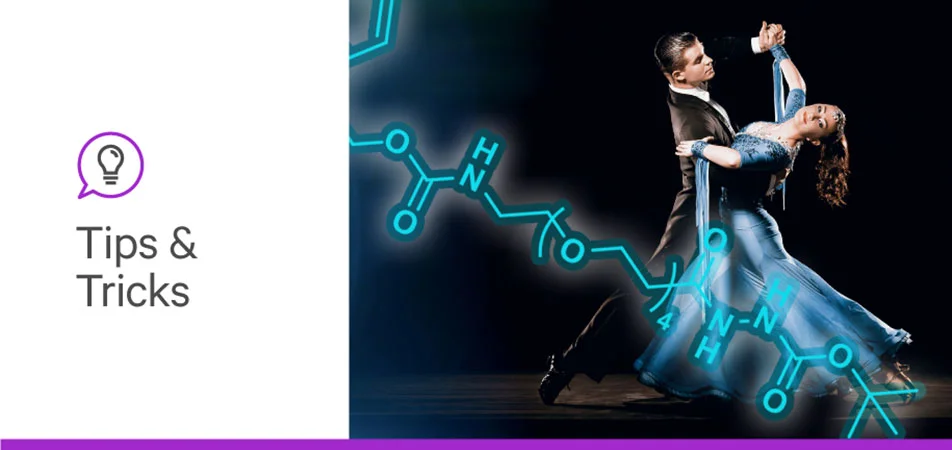

Figure 2: Commonly used sulfur-containing compounds for attachment to gold surfaces such as quantum dots.

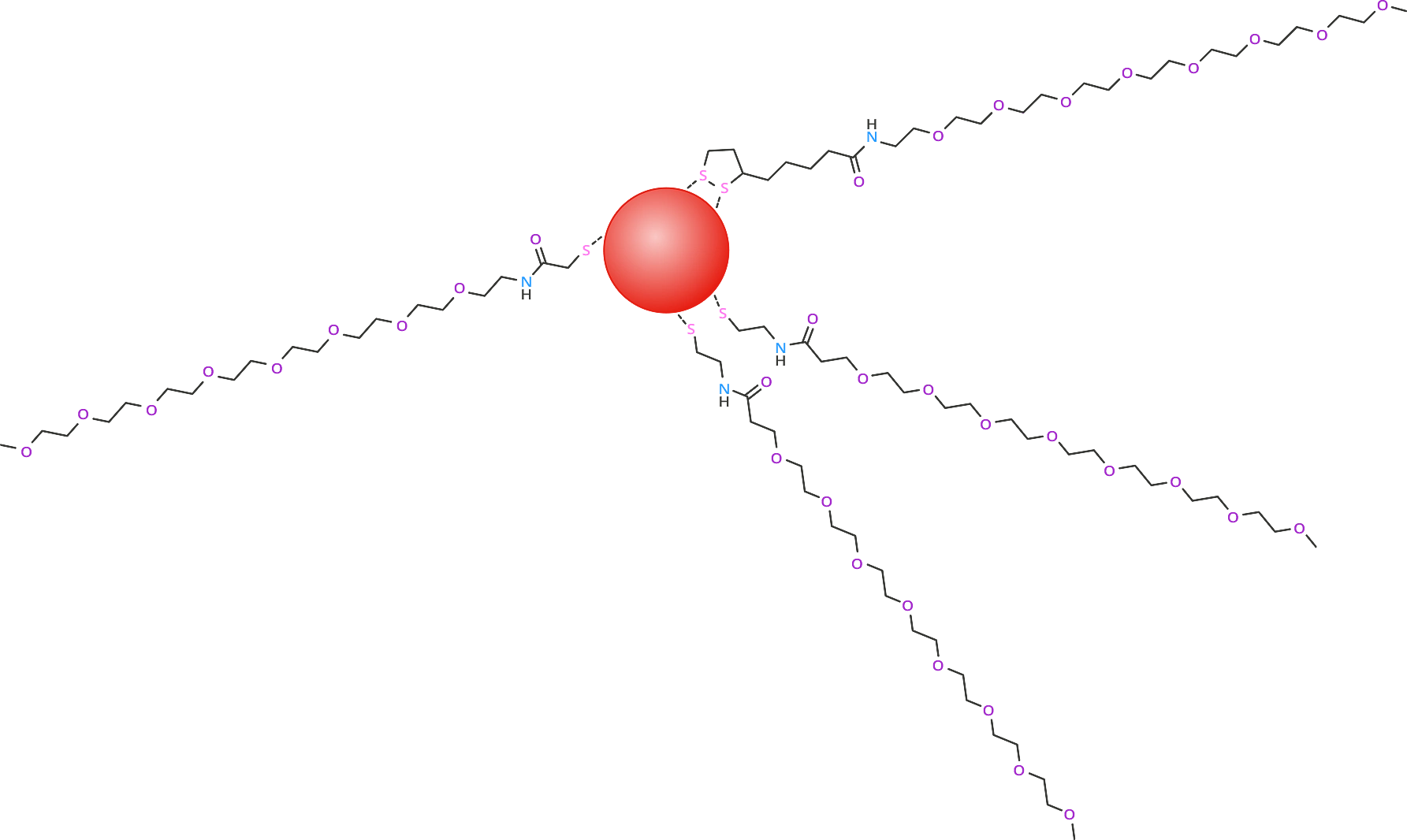

While these modifications allow for increased hydrophilicity, the water solubility can be increased even more by adding a dPEG to the acid or amine end by a simple coupling using 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC). Alternatively, a thiol-dPEG could also be used directly on the surface of the quantum dot. Figure 3 shows dPEG compounds attached to a quantum dot either directly or coupled to a thiol monomer already on the surface.

Figure 3: Red Quantum Dot (approximately 6 nm diameter) with Attached dPEG compounds m-dPEG®8-lipoamide (PN10800), m-dPEG®8-acid (NHS ester) (PN10324, PN10260 – coupled to cystamine) and m-dPEG®8-amine (PN10278 – coupled to mercaptoacetic acid)

Elizabeth L. Bentzen, et al., studied the effects of PEG on nonspecific binding associated with quantum dots and found that PEG as small as PEG350 (approximately dPEG8), when coated over the surface of quantum dots, can reduce nonspecific binding in certain cells [3]. The results showed that, in the cells studied, the PEG length could possibly be shortened to 12 units without increasing the nonspecific binding. Using a dPEG in place of a traditional polydispersed PEG gives the advantages of lot-to-lot reproducibility and confidence in the identification of the final product.

Stay in the Loop. Join Our Online Community

Products

Ordering

About Us

Application

Resources

©Vector Laboratories, Inc. 2025 All Rights Reserved.

To provide the best experiences, we use technologies like cookies to store and/or access device information. Consenting to these technologies will allow us to process data such as browsing behavior or unique IDs on this site. Not consenting or withdrawing consent, may adversely affect certain features and functions. Privacy Statement

Figure 1: TOPO coated green quantum dot (approximately 3 nm diameter).