Finding resources (especially on the financial side) has been an ongoing challenge. To start, as a non-traditional immigrant student, Jose had no initial access to financial aid. Fortuitous or not, he was too busy to complain, and he was steadfast in his commitment to graduating. He refused to have an excuse NOT to graduate. He began building an arsenal of emotional intelligence that plays a large role in how he approaches his life, reminding him to focus on changing the aspects that are within his control. He compensated for a lack of resources by borrowing books from the library, seeking additional funding for his education, working as needed, living at home, cooking his own meals and finding free food sources, and more. Eventually, when the state changed its laws in regard to immigrant students, he was able to access in-state tuition rates and financial aid, and earned a BS in Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology from UCLA in 2015.

“I honestly didn’t know what to expect from grad school. The brochures don’t tell you much. As an undergrad, I knew I wanted to do something in research, but didn’t know how. I thought about going to medical school, but I didn’t have money to apply or to pay if I was accepted. My undergraduate research mentor suggested that I should apply for a PhD. Then, if you get in, they pay you. That was something that I didn’t know. I was thinking about being a research assistant to find some stability after college. I applied and was accepted at several places but decided to attend a private research institute (here at City of Hope) because they gave me more funding opportunities and I wanted to have 1-on-1 mentoring that smaller institutions can give.”

Fast forward to today, Jose is working toward his thesis. After a few years in a situation that was not the best fit for him, he switched labs, finding a mentor who uses a constructive approach to build up confidence, rather than the destructive approach—still in use by some academics—that had affected his confidence throughout his youth. The positive approach works well for Jose, because he can often see more than one way to do things—devising new methods that don’t always align with traditional, scientific, or logical order—having an advisor who gives him the freedom to explore while providing valuable constructive feedback, creates an environment in which Jose can learn and grow.

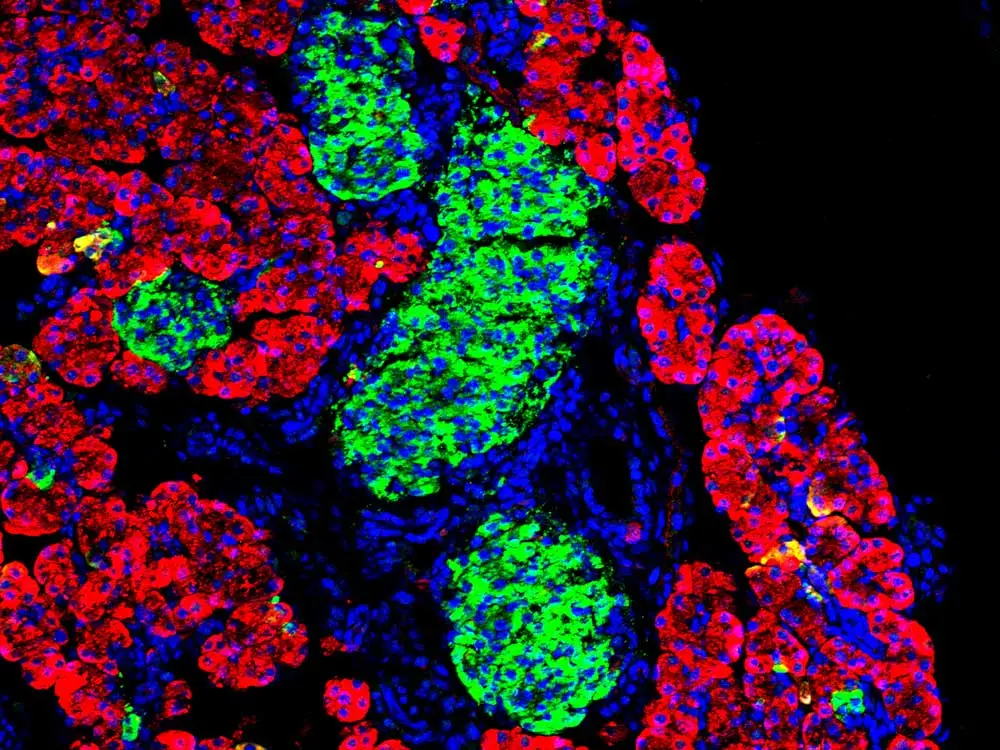

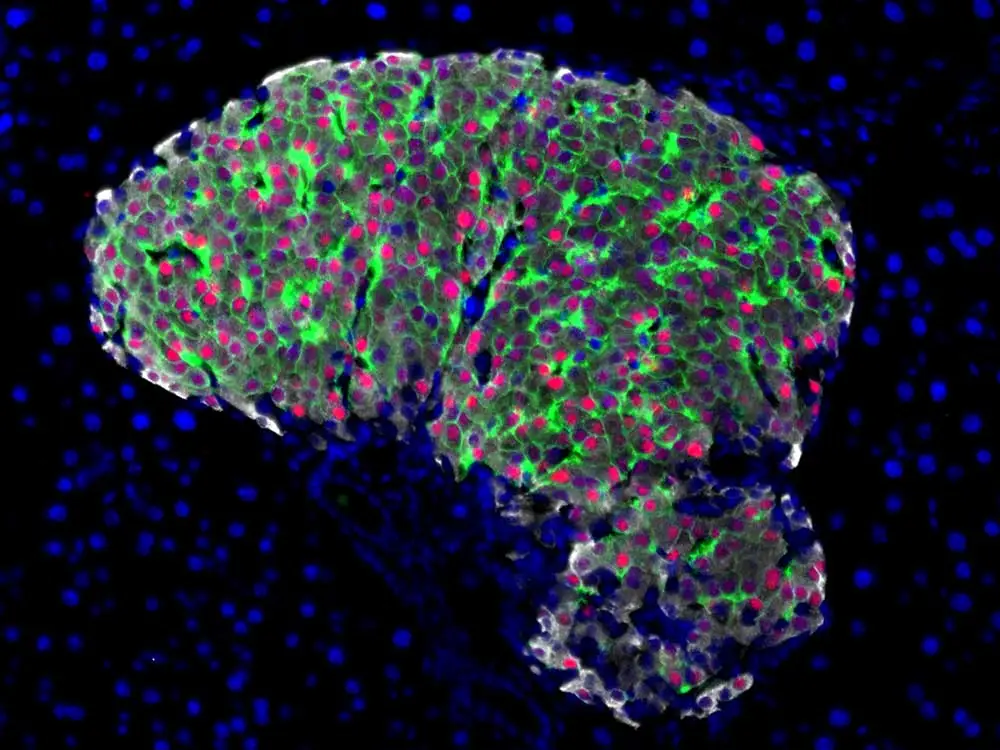

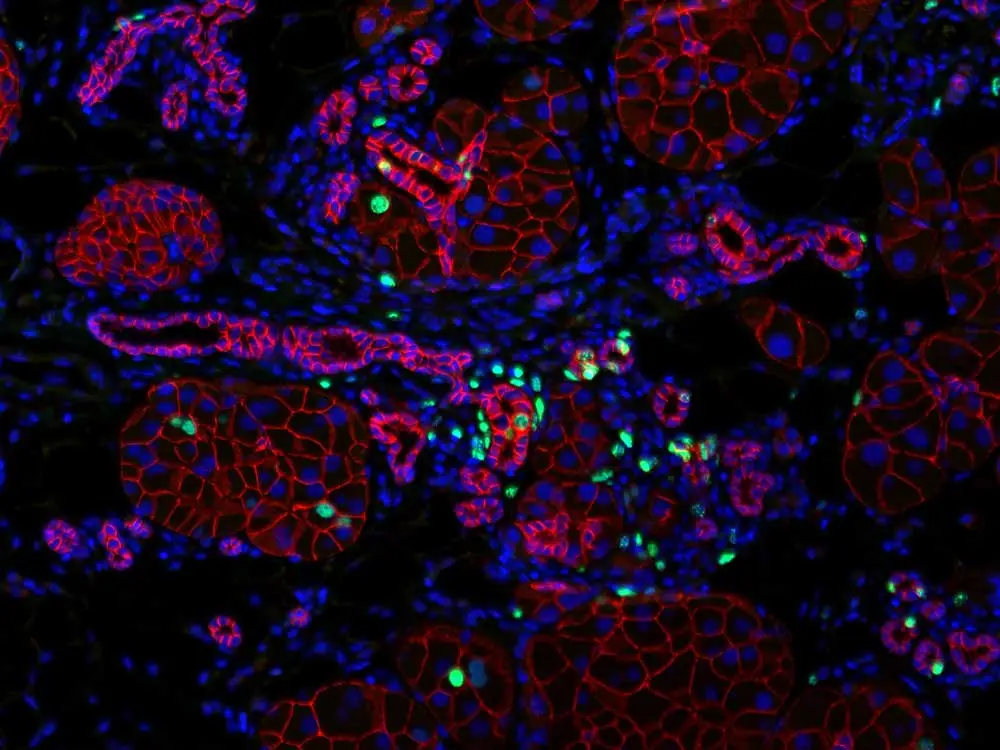

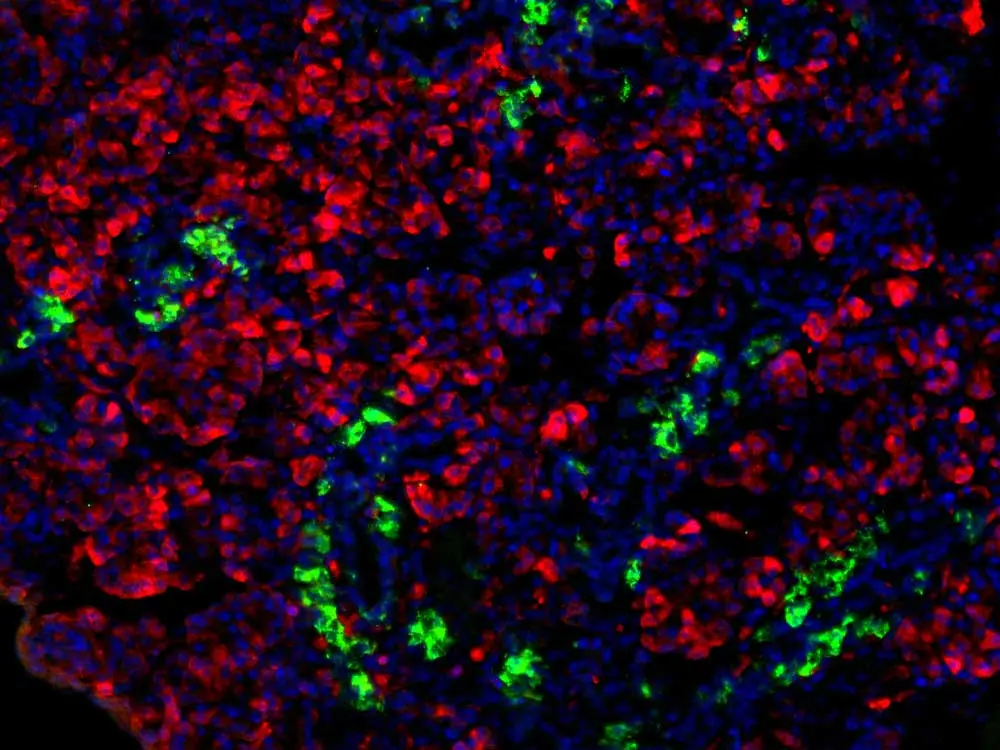

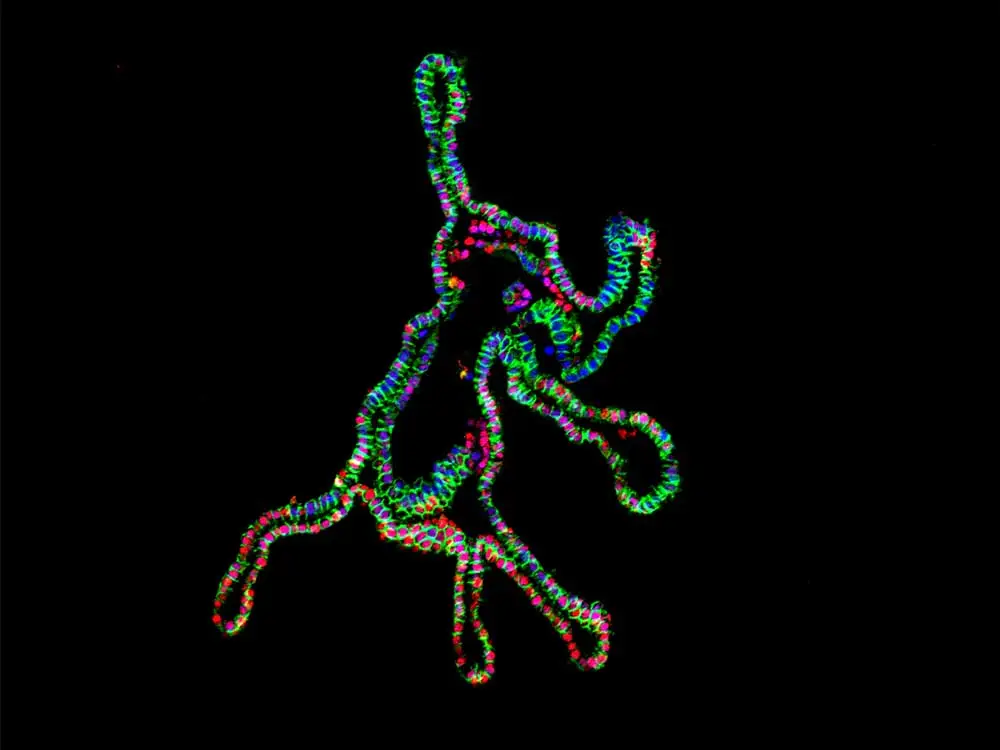

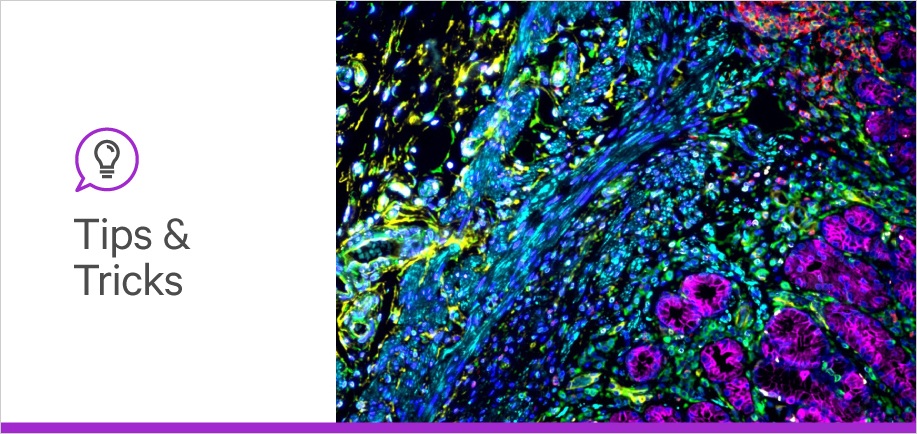

Diabetes research is one of the many programs supported by the City of Hope that aligns with Jose’s societal benefit goal. He’s studying pancreas organ development and regeneration, spending his days (and nights) thinking about intestinal growth factors and insulin-producing β and islet cells. He describes himself as “very visual” and might have pursued art “if he could have figured out how to make money at it.” Inadvertently, by using immunofluorescence to show the location of protein, he is using art in his career and sees not only the beauty and complexity in it but also the knowledge it communicates. He also finds satisfaction from the unique experience it provides: as the first person to see it, he gets to choose how to explain it.