Vector Laboratories is closed for the President’s Day on Monday, February 19th. We will be back in the office on Tuesday, February 20th.

We will respond to emails upon our return. Have a wonderful day.

Menu

Vector Laboratories is closed for the President’s Day on Monday, February 19th. We will be back in the office on Tuesday, February 20th.

We will respond to emails upon our return. Have a wonderful day.

Like many of you, Rosa was a curious and observant child. She learned to look beyond the obvious and sought answers to all kinds of questions. Even Santa seemed to know that giving young Rosa a microscope would introduce her to a world of discovery and foster her growing interest in biology. Her family was amazed by her curiosity and encouraged it as she grew up in Italy. While pre-collegiate science classes relied heavily on textbooks and tests, Rosa yearned for more hands-on experience in the laboratory, which she was finally able to sample on campus at the University of Naples Federico II. There she earned a BSc in General, Molecular and Cellular Biology, an MSc in Molecular Biology, and a PhD in Biology-Cancer Biology, all in the same laboratory. She served as a Visiting Researcher for a short stint in cancer research at the University of Edinburgh (Glasgow, Scotland) before heading to California in 2018. In her dreams, this would be where she could feed her soul, relish the beaches that remind her of home, and experience the seemingly endless research opportunities. She has been working passionately on postdoctoral research projects in tumor metastasis at the Moores Cancer Center (University of California, San Diego) ever since.

I think it may be a common story, but when I was a child, I was always super curious. So, I think it’s my personality that makes it a good fit for doing research. Even as a child, I have always been very observant and able to notice details. I was always curious about how things worked, so I was always asking myself and others why is this thing happening, why does this phenomenon exist, or stuff like that. When I was a kid, I asked Santa Claus for a microscope and quickly saw that with a microscope.

I could see things that my eyes alone can’t. And so, I was passionate about biology from the first time that I started to study it. I was also fascinated with history and archaeology. I saw being a biologist or an archaeologist as my ideal job because both required the curiosity that I had to make a discovery. Both had the potential for excitement and the ability to discover something new, but in the end, I decided that biology was right for me.

I’ve been in San Diego for 4 years now. I love this place. Honestly, it was the dream of my life, to come from Italy and live in California. As part of my PhD program, I had the opportunity to spend 6 months outside Italy so I was looking at several labs that I could join. I first thought about a lab in San Francisco, but in the end, I decided to join a cancer research lab at the Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. The Institute of Genetics and Cancer is a strategic partnership of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Human Genetics Unit (HGU), Cancer Research UK Edinburgh Center, and the Centre for Genomic and Experimental Medicine. I had a fantastic experience in Edinburgh but when I went back to Italy after discussing my PhD, I was still thinking about needing to go to California to work. I believed that I could have a well-balanced lifestyle and access to job opportunities within a strong research environment. They say that California and San Diego are perfect because they also have beaches, which help you achieve a nice balance. My other alternative was in Boston. And while I loved the research they were doing, I was not very excited about their much colder climate. In some ways, I think destiny was involved because whenever I looked at the location of the affiliation of the people authoring a paper, it was always La Jolla, La Jolla, La Jolla. And then after I checked what this area looked like, I said, “Wow, this is wonderful, I want to go there.”

When I went to middle school and high school in Italy, we didn’t have laboratory science classes where you could do practical experiments. We studied a lot, but only with books and both oral and written tests. I never had the opportunity to work in a lab until I went to university. My initial response for each college lab was that it was super exciting! Unfortunately, our lab sections were not very long, and we didn’t have many during the year. But to get a PhD in Italy, we must first earn both a Bachelor’s and Master’s degree. And for each, we need to write a research thesis, requiring us to join a lab, follow a project, and write about those experiments.

For my Bachelor’s research, I did three months of laboratory research with a team focused on cancer research. Initially, I was excited about the genetics and molecular biology focus of the work. But, for personal reasons associated with the events that were happening in my life, I grew to understand that I wanted to do science to help people. In my family, a lot of people die of cancer. I get a little bit emotional when I think about that because I know first-hand what happens to a person with cancer and how it affects their family. We were working on a tumor suppressor protein, and I had a nice experience—you can tell because I worked there not only through my Bachelor’s and Master’s programs but also for my PhD, which allowed me to see this project grow. And so, I’m (still) attached to that project, the team, and the place. Looking back, I think it was the best school for me to learn how to work in science.

In our labs in Italy, we didn’t have enough money to do the work—there were funding issues all the time. But there’s a lesson to be learned in that: when you don’t have many resources, you develop the skills you need to adapt and learn to accept the things that you can do. But to me, it made me question why we should do these experiments or figure out whom we could ask for a reagent when we didn’t have it. It was complicated. But it also gave me a push to want to do more and find a better situation when possible. You need to be able to adapt when something goes wrong. And, unfortunately, one of the main problems in science is the availability of funding: even in the best lab, there are periods when you know that the funding is going to expire, and you need to adapt to a stricter budget for a short time. And to me and where I come from, you give value to each thing, you don’t throw a thing away, and if there is an issue, you find a solution.

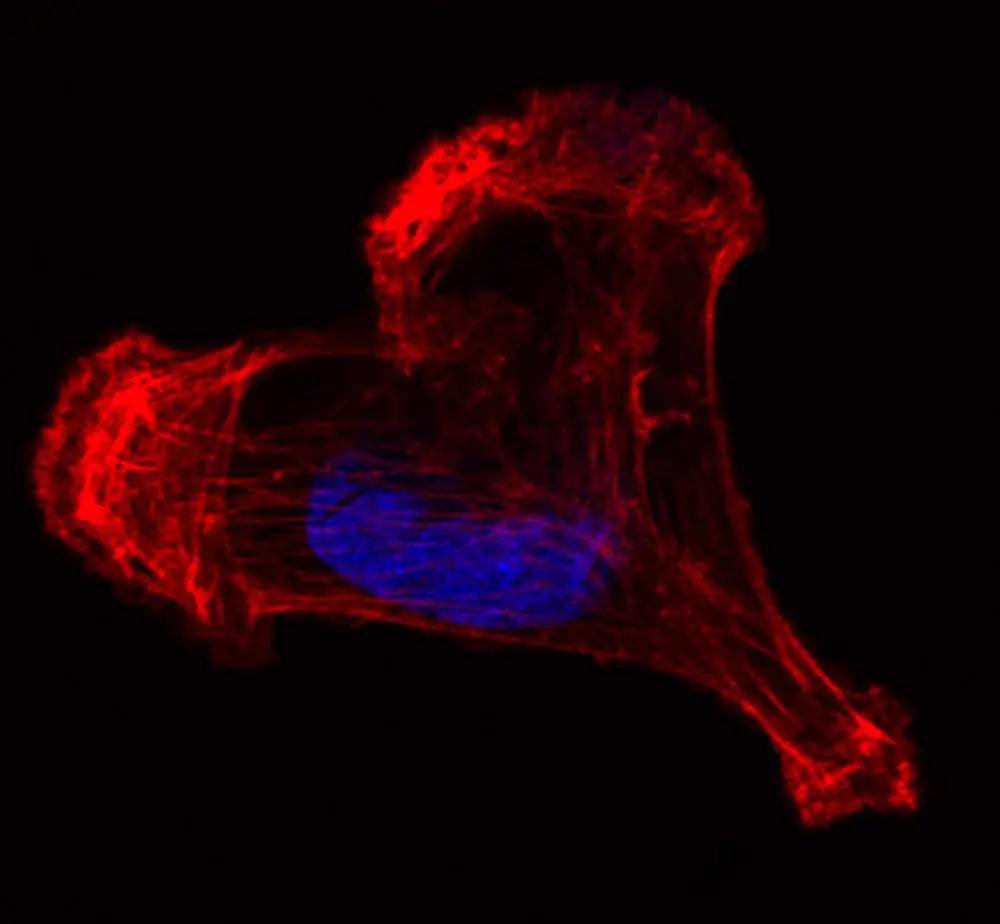

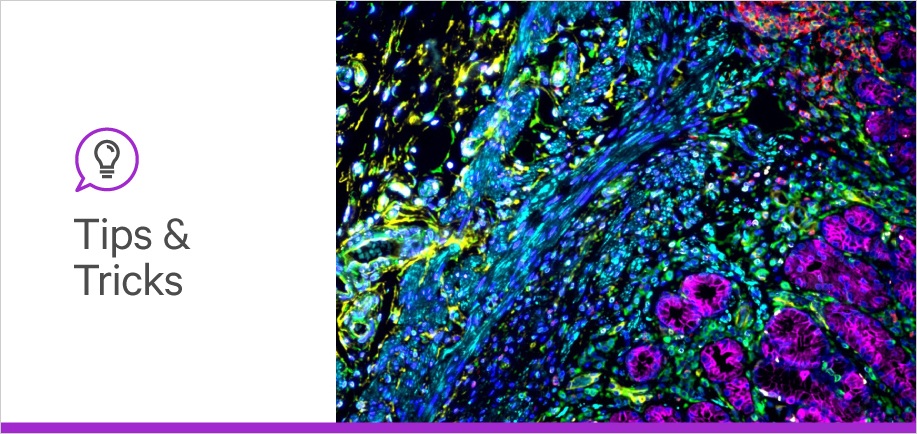

I joined this lab to work on tumor metastasis. While they have strong expertise in breast cancer, they also have subgroups that are each looking at a different aspect of tumor metastasis. My subgroup is looking at the actin-based structure that carcinoma cells form to degrade the extracellular matrix, invade, and metastasize. My project’s goals are to understand the molecular mechanisms, identify new proteins that affect this subcellular structure or the metastatic cascade, and find a new therapeutic target in the long term. What excites me about it is that this could translate into a positive impact on a cancer patient. We are still assessing which kind of cancer to focus on so that I can analyze the right kind of target, and we have resources available for that. And the project itself is interesting from a molecular biology standpoint. Also, the mechanisms of these small and highly dynamic structures are difficult to study, so having good microscopy skills is essential. We are developing good resources for live imaging and confocal microscopy in cancer cells.

It’s something that I’m learning here, to have this good balance between my work and life. As I see with my colleagues who do research in academia, a lot lose focus on themselves. They are too involved with only doing science. But having a 100% science focus can result in a loss of enjoyment for both your life and your science.

I don’t know. I haven’t decided yet because everything depends on how all this research right now will go. I’m still evaluating the possibility of a career in academia or sometimes I also think about the job of an editor, reviewing papers, or maybe a job in a biotech company to develop a product that can be helpful to treat patients. I need to think more about my future direction in science. I’ll be a postdoc at least until next October. Unlike in Italy, where careers in science are limited to academia and that’s it, in the US, there are a lot of different kinds of jobs that you can do with a PhD in biology: you can be what you want and change your career path anytime along the way just by a little bit or by a lot.

I can tell you that my best memories of my previous lab are related to passion. While the people were going to work and coming to the lab day after day, year after year, everyone was motivated by their passion. When this happens, it feels like there is a mental interaction, a strong connection. When that happens, you feel comfortable messaging each other in the evening to share ideas. And honestly, I would be happy if everyone in life could have this kind of experience. When you can find someone that is on the same wavelength in your job, it’s the best feeling that you can have. You know that that person thinks similarly to you. And when you interact with her or with him, the conversation can go on for hours. And while it’s job-related, you don’t think of it as work because you are talking about your passion.

Reward is the feeling that I have when I am discovering something, and that is one of the best feelings. You can especially see it at the end of a project when you pull the story together in a publication. I also love the rewards of communicating with people and talking about science: sharing ideas, hearing what others think, seeing how people react, and taking suggestions. I see communication as a moment of interaction with others and not as a moment where they are judging you. Because I think that science is all about teamwork, one of the best parts of this job is interacting with others that you work with day-to-day and side-by-side. Being open to suggestions from others who might be able to see something that you don’t notice can provide a new way to look at things. And that is even more rewarding.

I learned that you need to be persistent, but not fixed. A lot of people in this job can get fixed on some concept and then they spend a month or year or more on it rather than accepting that it just doesn’t work. It can be difficult to separate the failure of an experiment or a negative result from who you are and how well you understand the science. I couldn’t do that during my PhD, but I’ve gotten better since then. Now I try to focus on the main goal and find alternative ways to solve issues. This fosters discovery, and that’s what I do.

Stay in the Loop. Join Our Online Community

Together we breakthroughTM

©Vector Laboratories, Inc. 2024 All Rights Reserved.